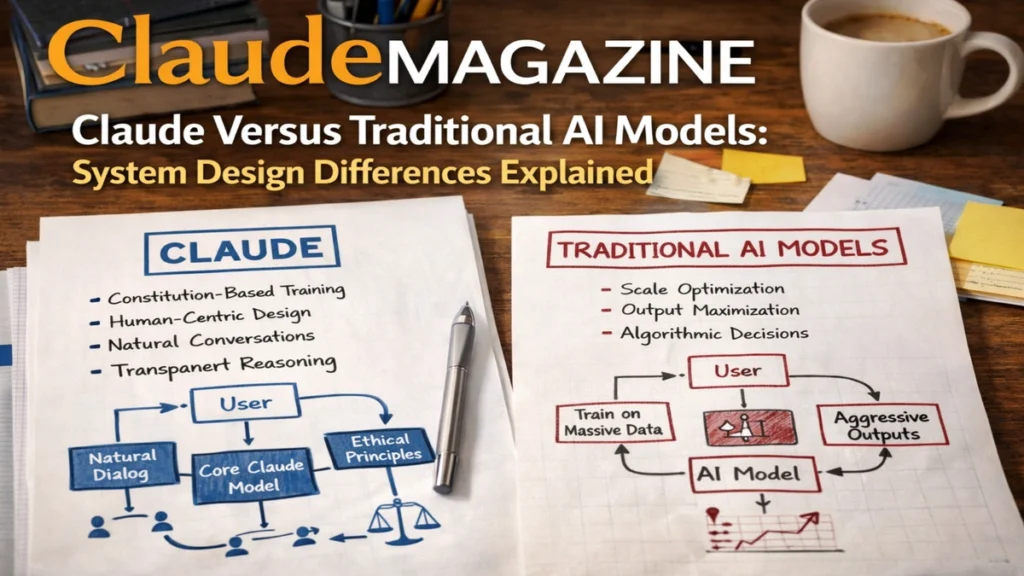

i have learned that most “model comparisons” fail because they compare only outputs, not the system choices that shape those outputs. Claude and traditional AI models often share the same underlying engine: a transformer trained at scale to predict the next token. That base similarity is real, and it explains why both can write, summarize, code, and reason in broadly comparable ways. But the difference people feel in everyday use rarely comes from the transformer itself. It comes from how the assistant is trained to behave, how it handles risk, and how the product expects humans to stay in control.

Claude is designed as a constitutional, human-aligned assistant rather than a generic text predictor that is later fenced in. In practice, that means the system is built to prioritize safe defaults, steady tone, and explicit boundaries. It is also tuned to treat refusal and uncertainty as acceptable outcomes, not embarrassing failures. Traditional models, especially earlier chat-style assistants, often answered by default and relied more on external safety layers, post-filters, or ad hoc moderation to catch problems after the model produced them. That difference changes how the assistant responds when a user asks for something dangerous, ambiguous, or ethically fraught.

This article explains those system design differences in a grounded way. I focus on the shared architectural foundation, then move to the decisions that separate Claude from more traditional approaches: Constitutional AI versus standard RLHF, safety-first default behavior, role framing, long-context collaboration, and permission-based workflows like Claude Code. I also cover the practical consequences: why Claude can feel more trustworthy in high-stakes deployments, why it can feel more conservative in borderline scenarios, and how refusal-aware product design can reduce friction without weakening guardrails.

The Shared Foundation People Overrate

Claude and many traditional AI assistants start from the same basic paradigm: a large transformer language model trained on massive text corpora to predict the next token. This matters because it sets expectations. Both systems can generate fluent language, follow instructions, and adapt style based on context. Both can be offered as a “family” of models, with different tiers optimized for speed, cost, and depth. Both can be extended into tool-using workflows that resemble agents.

This is also why it is misleading to frame Claude as a totally different kind of machine. The meaningful contrast is not “Claude uses an entirely different architecture.” The contrast is that Claude’s designers emphasize system-level alignment, safety posture, and interaction design as first-class product requirements. Traditional models often treated safety and alignment as constraints layered on top of a capability-driven core. That difference can be subtle in a casual chat, but it becomes obvious when the user asks for risky instructions, when the task is ambiguous, or when the output will be used in a real workflow that has consequences.

In short, architecture explains capability. System design explains behavior.

Read: Claude’s Language Architecture: Why Tone, Structure, and Clarity Matter

Traditional RLHF and the “Answer by Default” Habit

Traditional alignment in mainstream assistants is often associated with RLHF, reinforcement learning from human feedback. In this approach, humans label or rank outputs, then the model is tuned to prefer the answers humans rate as better. RLHF works well for teaching instruction-following, improving tone, and reducing obvious toxicity. It also helps models learn conversational norms that make them feel responsive and coherent.

But RLHF has limits that show up in edge cases. Human feedback is expensive and hard to scale to every domain, every culture, and every adversarial tactic. Human raters can also reward superficial helpfulness in ways that unintentionally push models toward confident completions even when evidence is weak. That is one reason older assistants developed a reputation for “confident hallucination,” especially on obscure topics or under vague prompts. The model learned that sounding helpful often beat admitting uncertainty.

Traditional systems often compensated by adding external safety layers: policy filters, moderation classifiers, blocked keyword lists, and other guardrails outside the core model. Those layers can be effective, but they can also produce inconsistency. The model might generate an answer that a filter blocks, or it might produce borderline material that slips through because the safety layer did not recognize the nuance. The user experiences this as uneven behavior, shifting tone, or sudden refusals without clear explanation.

This is the environment Claude tries to improve: fewer surprises, more stable boundaries, and safer defaults.

Constitutional AI as a Design Philosophy

Claude’s defining difference is less about raw intelligence and more about how the assistant is trained and framed. The core idea is Constitutional AI: a written set of principles that guides critique and revision so the model learns aligned behavior without requiring humans to label every possible harmful edge case. In practical terms, the system uses principles like non-harm, honesty, non-manipulation, and respect as a consistent internal rubric.

This changes the assistant’s default behavior. Refusal is not merely a last-minute safety intervention. It becomes a learned pattern that is part of the assistant’s identity. The system is trained to explain boundaries, redirect harmful requests, and prioritize safe alternatives. Instead of treating safety as a separate subsystem, Constitutional AI aims to build safety-aware behavior directly into the assistant.

That does not mean Claude refuses everything. A refusal-only system would be harmless but useless. The goal is a model that is safe without becoming evasive, helpful without becoming enabling, and honest without becoming hostile. The tension between those goals is where system design matters most.

Safety-First Internal Behavior and Uncertainty as a Feature

One of the most visible differences between Claude and many traditional models is how they handle uncertainty. Claude is more likely to say, “I’m not sure,” or to request clarification when the prompt is ambiguous. That is not just a personality choice. It is a safety and honesty preference that reduces the chance of confident invention when evidence is missing.

Traditional assistants, especially earlier generations, often tried to complete the user’s request even when key details were absent. When a user asks about a “new law” with no jurisdiction or date, the model has to guess. If the system rewards helpfulness more than caution, it may fill in plausible details based on general patterns. That is how hallucinations happen: not because the system wants to lie, but because it is trained to keep going.

Claude’s conservative posture reduces that pressure. It treats uncertainty as acceptable, and sometimes preferable, because the downstream risk of a wrong answer can be higher than the short-term benefit of a fluent one. This posture is particularly valuable in enterprise settings where the cost of a mistake is real: legal decisions, financial guidance, medical discussions, security-related tasks, or brand-sensitive communications.

At the same time, that conservatism can create friction when a request is legitimate but poorly framed. That is the core trade: fewer harmful or reckless outputs, but a higher skill floor for prompts in borderline domains.

System Prompt and Role Framing as a Behavioral Backbone

Claude tends to feel steadier in tone than many traditional assistants. This is not accidental. Claude is framed as an assistant with duties, not merely a text generator that happens to be chatty. Role framing matters because it shapes how the model interprets the user’s intent and how it resolves conflicts between user convenience and broader safety or ethical concerns.

Traditional chatbots often began with simple role prompts and layered policies externally. That approach can work, but it can also lead to variance in tone and boundary-setting. When the “assistant identity” is thin, the model’s behavior can swing more under emotional, adversarial, or flattering prompts. That can show up as over-agreement, inconsistent refusals, or sudden shifts into moralizing language.

Claude’s system design emphasizes steadiness: measured tone, clear explanations, and boundaries that do not depend on whether the user sounds polite or aggressive. This does not make Claude perfect. It does make its behavior easier to design around, because the assistant is less likely to be “talked into” crossing lines through rhetorical pressure alone.

Long-Context Collaboration vs. Shallow Recall

Claude is widely used for long-document tasks: summarizing lengthy reports, analyzing policies, reviewing contracts, reading codebases, and tracking multi-step reasoning. The important point is not that Claude alone can handle long context. It is that Claude is optimized and positioned for it as a core use case, and that system posture shapes how it behaves.

Traditional models with smaller or less-optimized context windows often rely more on broad priors when the input becomes long or ambiguous. When details are buried, the model can drift into generalization and lose local constraints. That is where hallucination risk rises and where users start to mistrust the output, even if the writing is fluent.

Claude’s system design combines large-context collaboration with conservative uncertainty behavior. When context is long, it is easier to make subtle mistakes. A model that is willing to surface uncertainty and ask for clarification is easier to audit. A model that tries to sound certain under all conditions is harder to trust.

This is why Claude is often used as a document and code reasoning partner rather than a quick-answer engine.

Interaction and Workflow Design: Claude Code as a Case Study

Claude Code illustrates a broader design philosophy: collaboration over silent automation. In a coding context, risk is not theoretical. A single destructive command or careless edit can cause outages, data loss, or security exposure. Claude Code is designed around human-in-the-loop guardrails, incremental changes, and permission-based control.

Traditional “AI coding” started as chat-based code generation or autocomplete. Those tools can be productive, but they often lack explicit review loops and permission gates. The user might paste code, ask for a feature, and receive a full file replacement. The model may not be required to ask before making changes, because the system is not actually executing anything. Once AI tools moved closer to the terminal and the repository, the safety problem became immediate.

Claude Code leans into that reality. It encourages small, reviewable diffs, asks before sensitive actions, and fits into existing engineering habits: branches, pull requests, tests, and code review. This is not merely a product feature. It is system design aligned with human accountability.

The result is a different relationship. The model becomes a co-pilot in a process the human still owns, rather than an automator that quietly “does it all.”

How Claude Differs From Traditional Models in Practice

| Design Area | Claude’s System Posture | Traditional Patterns Often Seen |

|---|---|---|

| Alignment method | Constitutional principles guide critique and revision | RLHF focused, with external filters for safety |

| Default behavior under risk | More likely to refuse, redirect, or ask for clarification | More likely to answer, then rely on post-filtering |

| Uncertainty handling | “I’m not sure” is acceptable and common | Historically more confident completion |

| Tone under pressure | Measured, explanatory, consistent boundaries | More variance under adversarial prompting |

| Tool workflows | Permission gates, incremental diffs, human review loops | Often fewer explicit oversight mechanics |

This comparison is not a moral judgment. It is a design map. Each posture fits different product goals and different risk profiles.

The Trade-Off: Default Refusal Builds Trust, But Can Cause Friction

Claude’s default refusal posture has strong benefits. It lowers the chance that ambiguous prompts produce harmful instructions. It increases deployer confidence in regulated or brand-sensitive environments. It teaches users that boundaries are consistent, which reduces incentives to probe and bypass.

But the cost is real. Over-refusal can block legitimate work, especially in domains like defensive security, policy analysis, or ethical debate where users need to discuss harmful topics without intending harm. Poorly phrased requests can trigger conservative safety behavior even when the user’s goal is responsible.

This is where product design matters. If an application assumes “the model always answers,” refusals become silent failures. Features break. Users get stuck. The refusal becomes a low-cost denial-of-service vector in the user experience, even when the model is doing what it was trained to do.

The remedy is not to remove refusals. The remedy is to design for them.

Refusal-Aware UX: What Good Systems Do

Refusal-aware systems treat refusal as a structured outcome, not a dead end. They detect refusal patterns and present clear next steps. They guide users to clarify intent, offer safer alternatives, or route high-risk tasks to human review.

In content workflows, this might mean prompting the user to specify whether the request is for reporting, safety education, or policy analysis. In security workflows, it might mean offering high-level defensive guidance while requiring explicit safeguards for anything that could enable misuse. In customer support, it might mean escalating to a human agent when a request crosses policy lines.

This approach protects the assistant’s safety posture while reducing user frustration. It also makes the product more resilient, because it can handle “no” as part of normal operation.

Positioning in the LLM Ecosystem

Traditional model positioning often emphasizes raw capability: benchmark wins, creativity, broad knowledge, and speed. Claude’s positioning emphasizes ethics, safety, and quality as first-class goals, while still competing on reasoning and language performance. That difference in marketing reflects a deeper difference in system priorities.

In practice, Claude can feel more conservative on edgy or speculative topics. But it can feel more robust in safety-critical deployments, where consistent boundaries, transparent uncertainty, and stable tone matter as much as cleverness. For many organizations, that trade is worth it. They would rather have an assistant that sometimes says no than an assistant that says yes and creates liability.

The point is not that one model type is universally superior. The point is that system design determines which risks you accept and which risks you reduce.

Three Expert Quotes That Capture the Difference

“Architecture is the engine, but policy is the steering wheel.”

“Refusal is not failure when the alternative is harm.”

“Trust grows when uncertainty is visible, not hidden behind fluent prose.”

These lines summarize what teams learn after deploying assistants in real systems. Capability is necessary. Governance is decisive.

Takeaways

- Claude and traditional models share the transformer foundation, but differ sharply in alignment and system design choices.

- Traditional RLHF aligns behavior through human preference signals, while Constitutional AI uses written principles to scale critique and revision.

- Claude’s default posture favors safety and uncertainty over risky completion, which increases trust but can create friction.

- System prompts and role framing shape tone stability and boundary consistency under pressure.

- Claude Code reflects a collaboration-first philosophy with permission gates and incremental changes.

- Products that expect refusals and handle them explicitly regain usability without weakening guardrails.

Conclusion

i have come to see the Claude versus traditional model comparison as a lesson in product architecture, not just machine learning. If two assistants share the transformer base, their visible differences come from how they are trained to weigh safety, honesty, helpfulness, and user intent. Claude’s system design leans toward conservative defaults, steady tone, explicit boundaries, and workflows that keep humans accountable. That posture can feel slower in the moment, especially when a user wants a fast answer and the system asks for clarity. But it is also the posture that makes large-scale deployment safer in environments where mistakes have consequences.

Traditional assistants can feel more flexible, especially in open-ended brainstorming or speculative conversations. Claude can feel more disciplined, especially in domains where “maybe” is safer than “sure.” The best choice depends on the job, the risk, and the system you are building around the model. If you treat the assistant as a collaborator within a process, Claude’s design shines. If you treat it as an always-on answer machine, you will fight its boundaries. System design decides which relationship you get.

FAQs

Is Claude a different kind of neural network than other assistants?

No. It is still a transformer language model. The major differences come from alignment and product design choices.

What is the practical meaning of “Constitutional AI”?

It means the assistant is trained to critique and revise outputs using written principles, scaling alignment without labeling every edge case.

Why does Claude refuse more often than some traditional assistants?

Claude is designed with safer defaults, especially when a request is risky or ambiguous. It often prefers refusal or clarification over guessing.

Can over-refusal be reduced without weakening safety?

Yes. Refusal-aware UX can guide users to clarify intent, offer safe alternatives, or route high-risk tasks to human review.

Which model type is better for enterprise use?

Enterprises often value safety, stable tone, and auditability. Claude’s system design targets those needs, but product context matters.